ZOMG Nuclear Meltdown! Wait, What Does That Mean?

First off, what happened in Japan is horrible. I do not at all mean to downplay any of the tragedy that occurred there. Also, I do not claim to be an expert on nuclear technology. However, I do know a fair amount, and more than enough to be able to distill what others (such as the people at MIT) have written. And I like my friends to be informed, and able to call bullshit on media hype when appropriate.

So with that said, this nuclear reactor stuff has been generating a lot of buzzwords in the media, which I don’t think many people understand. If you don’t want to read all this crap, skip to the TL;DR section at the bottom.

What is nuclear meltdown?

That’s when the reactor goes out of control and there’s a nuclear explosion like in Chernobyl, right? Wrong.

That’s when the reactor goes out of control and there’s a nuclear explosion like in Chernobyl, right? Wrong.

It’s basically when the rods melt themselves, and their surroundings. That’s it. If complete nuclear meltdown is all that occurs, nothing bad happens. Well, except the company that owns the reactor will have to spend a lot of money to reclaim the uranium back out of the soup of melted crud inside the containment unit. And nuclear plants are engineered with multiple redundant levels of fail-safes, and further engineered such that even if all of that goes wrong, the damage will be minimal.

Also, let me side-track a moment to talk about Chernobyl. First off, it wasn’t a nuclear explosion — not in the sense of an atom bomb. Many things went wrong there, not the least of them was that the plant was poorly built. Also, it was not kept up very well. Also, it was understaffed. Also, the people who were on the staff made many bad decisions. What happened was that the core suffered meltdown, containment measures failed, and there was a non-nuclear, regular ol’ hydrogen/oxygen explosion that scattered radioactive crap everywhere. Essentially, it was a dirty bomb.

So what’s going on in Japan?

Okay, to know what’s going on, first you have to know a little about how nuclear reactors work. This will be a simplistic crash course. First, the 4 levels of containment:

- The uranium resides in little ceramic oxide pellets, about 1cm tall and wide. They have a melting point in the neighborhood of 2800 °C.

- Those reside in Zircaloy casings, forming fuel rods. Those have a melting point around 1200 °C.

- Those are put into what is essentially a big steel pressure cooker that operates at around 1000 PSI.

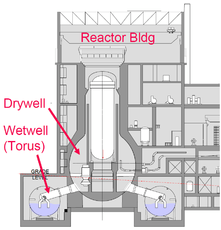

- The entire main loop of the reactor — the “pressure cooker”, pumps, and pipes that contain water (which is used as a coolant) — is housed in a thick concrete and steel casing.

- There’s technically a 5th level: the plant itself. But it doesn’t do much as far as containment goes, functionally speaking.

#4 is the big one. It’s made to contain a complete core meltdown indefinitely. So if a meltdown does occur, everything is contained in this (including the radiation), and inside is a soup of the rest of the crap.

When the earthquake started, control rods were dumped into the core to stop the reactions, but there are secondary reactions that take a while to wind down, so the cores will keep producing heat for several days in the meantime. Heat is normally good — nuclear reactors are kind of like big steam engines. They heat up the water, which turns into steam and spins turbines which produce electricity.

The earthquake that hit was several times the power of what it was built to take (the Richter scale is logarithmic, so a 9.0 earthquake is ten times as bad as an 8.0). That wasn’t so bad on its own, but then the tsunami hit.

All right, so what about the explosions?

Long story short, this caused the cooling systems to fail. It was a pretty epic fail, including instances of them bringing in backup power to keep the water pumping, but not having connectors to connect the power where they needed it to go.

So pressure was building — literally and figuratively. They needed to vent some gas outside of containment to alleviate that. Unfortunately, at those temperatures, the hydrogen and oxygen tend to break apart, which makes for a nice explosive mix. This wouldn’t normally be a problem because of the amount of water that is still in the air, but when it hit the cooler roof of the plant, some of the water vapor condensed, tipping the balance in favor of the combustible gases, and a spark somewhere made a boom. This happened in reactors 1 and 3 at Daiichi, and the boom was outside of containment. The more recent boom at reactor 2 was different, and of greater concern, but I’ll get to that in a minute.

Why vent gas from containment though? Isn’t that radioactive?

Well yes, it is… for a few seconds, literally, before it becomes safe. In some of the venting-induced explosions, some more-radioactive material got vented. At 9:37am (JST) the radiation level was around 3130 micro

Sieverts. That’s definitely not good, but to put that into perspective, if you were exposed to 100x that level for an entire day, you might feel nausea and have some damage to bone marrow. However, just an hour later, it had dropped to about 1/10th of that, and continued to drop off (albeit more slowly) after that.

So why the hubbub?

People hear radiation and possible nuclear meltdown, and it’s sensational. Which makes people watch the news. Which allows the news corporations to sell commercial time for much more money. From what I know, at this point there’s really only one thing to be concerned about:

Possible degradation of containment at Fukushima Daiichi Unit 2

Remember containment element #4 above; that thick concrete/steel casing? Earlier today (March 15th) it was reported that there was an explosion at unit 2 inside that primary containment unit, damaging the suppression chamber (a doughnut-shaped chamber holding water and meant to depressurize the core). This is more serious than the other 2 explosions. The gas causing the explosion should have been vented, and exploded outside of containment if at all (as with units 1 and 3), but for reasons yet unknown, it wasn’t vented, and it went boom inside of there. If the suppression chamber is damaged badly enough, I presume it means pressure will build again, faster, until there is a bigger boom. Which could end up being like Chernobyl.

Remember containment element #4 above; that thick concrete/steel casing? Earlier today (March 15th) it was reported that there was an explosion at unit 2 inside that primary containment unit, damaging the suppression chamber (a doughnut-shaped chamber holding water and meant to depressurize the core). This is more serious than the other 2 explosions. The gas causing the explosion should have been vented, and exploded outside of containment if at all (as with units 1 and 3), but for reasons yet unknown, it wasn’t vented, and it went boom inside of there. If the suppression chamber is damaged badly enough, I presume it means pressure will build again, faster, until there is a bigger boom. Which could end up being like Chernobyl.

TL;DR

So what does all that mean? The explosion before today were no big deal. The radiation released so far was no big deal. The explosion today could cause the shit to hit the fan, however.